One way to think about the word “theology” is through its etymology (where the word comes from). Theos (θεος) is the Greek word for “god.” The ending “-logy” is often translated as “the study of,” but the Greek word logoi (λογοι) actually means, “words.” Thus etymology suggests that theology consists of the words we use to talk about God. Although the object of study is God, the words are human words which we struggle to understand, define, and use.

The classical definition of “theology” was offered by Anselm in the eleventh century. He called theology fides quaerens intellectum, “faith seeking understanding.”

Notice that “faith” comes first. Theology, unlike religious studies (below), takes belief as a starting point. Belief is not so much the result of theology, but the beginning of theology. For most of us, faith is not something that we were talked into through a series of propositions and arguments. Rather, faith usually grows inside of us without our awareness, through our families, culture, and ultimately God’s own action. Theology usually takes some sense of faith as a starting point and builds from there.

“Seeking” is the key verb for what we are doing when we “do theology.” It is a process that never truly ends, but always brings us closer to something worthwhile. The Latin word quaerens is related to “query,” and fits the “questioning” theme of this course. We are asking questions and seeking meaning. We are building on the history of meaning that others have found. It is an ongoing quest, not a closed body of knowledge to learn.

It might be possible to have a heartfelt or intuitive internal understanding, but theology is an intellectual kind of understanding, as indicated by the Latin word intellectum. Intellectual understanding occurs in the mind and can be expressed in words. It is possible to have faith without understanding; my great-grandmother was a woman of remarkable faith even without theological education. The study of theology will not make you a better Christian than my great-grandmother. It is, however, an essential part of a well-rounded intellectual education.

Theology and Religious Studies are both important academic disciplines. It is possible to mix them, but basic differences remain. Secular public universities, such as the University of Texas, may include religious studies, but theology is mostly found in private universities.

Religious Studies aspires to neutrality in the study of religions, without favoring any one religion as more true or central than another. One can study the behavior of religious people and societies as a sociologist or anthropologist, without ever asking whether a god is responding to the prayers and rituals. One can study the literature of religious people without caring whether the Bible’s claims about Jesus are more relevant than Shakespeare’s claims about Hamlet. Religious studies takes religions as the object of study from without.

Theology studies a religious tradition from within. It can occur with awareness and consideration of other traditions, but it takes one faith tradition as a starting point. It should be fair, but it does not try to be neutral. It may build on historical knowledge of facts, but it seeks meaning beyond the scientific description of human behavior.

This course follows a path of questioning related to Christianity. Students in the class will learn more about the Christian tradition than they will about Islam or Buddhism. We do not aspire to cover equally every religion and way of thinking about God. However, the questions can be asked within any tradition, and the ability to think clearly and articulate ideas about God does not presume any one set of answers. A good grade will require knowledge of what others (mostly Jews and Christians) have thought; it will not require agreeing with them.

Catechesis means “teaching.” It usually means teaching the current set of answers to theological questions without too much concern for the history or diversity of thought on the issue. Catechesis is typical for teaching children the beliefs and practices of a faith tradition (especially if the child is not like me, always asking “why?”). Catechesis is also appropriate for adults who join a religion that they did not grow up with. More so than theology, catechesis is concerned with a single faith tradition, and only the present teaching.

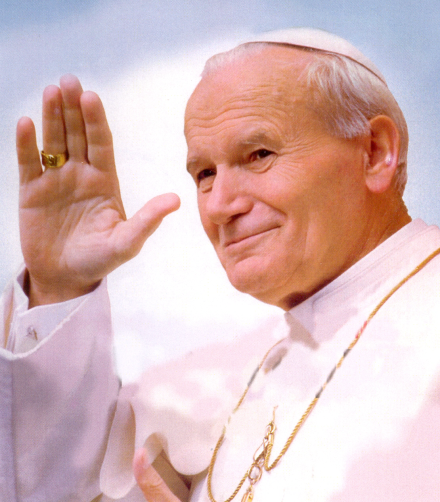

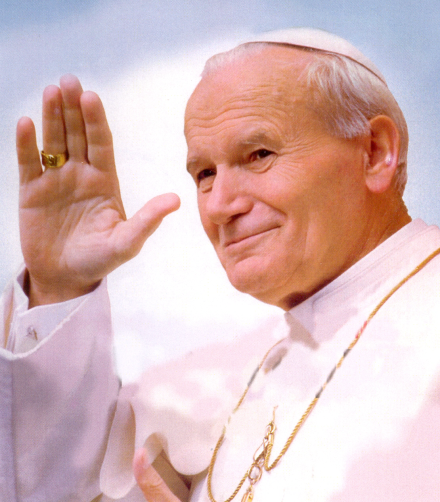

This course aspires to accurately represent the current Catholic teaching on major theological questions, but it will also include other perspectives. If it is important to you to keep straight what the Catholic Church currently teaches and align your thinking with the official thinking, you should be sure to have on your shelf a copy of The Catechism of the Catholic Church (or a link to usccb.org).

I think of catechesis as a snapshot of theology. Theology is an ongoing process. Many people over thousands of years have contributed to the tradition of teachings that make up the current teachings of the Catholic Church. Meanwhile, the process of theology continues to move forward, and in fifty years there will be a revised Catechism based on the work of theologians today. Theologians are aware of the past, articulate the present, and are ultimately responsible for building the future.

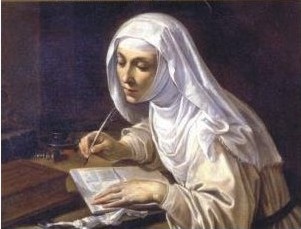

Many thinking, intellectual people of faith do theology, and also have other professions and titles. Someone whose main professional title is “theologian” probably spends most of the day teaching in a department of theology and writing books and articles that offer a deeper understanding of our past tradition, a better way of articulating our faith, or new ways of thinking about our faith. Like most professions, any one theologian has a basic knowledge of the field as a whole, and a specialization in a particular area.

There is no universal set of categories and titles for the areas of theology, but almost all theology programs would distinguish at least three major areas.

Biblical theology seeks questions and meanings from the Bible. This includes the ideas of the ancient authors of the Bible, but it also includes the history of interpretation. Over the past 2000 years, Jews and Christians have sought and found meanings in the Bible beyond what the human authors could have imagined. That is okay, particularly because almost all Jews and Christians recognize a Bible (there are different Bibles) as revealed or divine in origin in some way. Just as God cannot be fully grasped (though we can always try to get closer), the Bible is an endless source of interpretation and meaning beyond what any human comprehended in the past. In the Catholic Church the primary emphasis is on understanding the divine meanings of the Bible as expressed by particular human beings in particular historical contexts. Advanced study of the Bible involves reading the Bible in its original languages (Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek) and related ancient literature and history. At St. Mary’s the specialists in biblical theology are Drs. Hanneken, Ronis, Gray, and Whipple.

Moral theology focuses on how the Christian life should be lived through our moral choices. Moral theology builds on theory of sin, conscience, forgiveness, and reconciliation. Sometimes it involves firm teachings on specific moral issues, and sometimes complex ways of thinking about open-ended and ambiguous dilemmas. Two major sub-areas in moral theology are social justice and medical ethics. Social justice considers how a Christian should respond to injustices in the world, such as inequality (racism, sexism), and economic injustice (poverty, living-wage, social security). Medical ethics deals with the sanctity of life, particularly at its beginning (embryos and fetuses) and end (life support, euthanasia). At St. Mary’s the specialists in Moral Theology are Drs. Montecel and Ball.

Systematic theology focuses on articulating the traditional faith in light of new ideas in philosophy and culture. The term “systematic” refers to the idea that every individual belief should be consistent with every other belief, as part of a larger “system.” The biblical writers and great theologians of the past never really considered or faced the specific challenges of modern science, globalization of war and commerce, democracy, feminism, genocide, and so forth. Systematic theology tries to find a consistent way of responding to these challenges through engagement with the existing traditions of Christianity. At St. Mary’s the specialist in systematic theology is Dr. Mosely.

Some theology departments use additional categories, such as the history of Christianity, liturgical studies, and spirituality.

The major in theology at St. Mary’s calls for ten theology courses distributed between the areas of Scripture and Thought and Practice. The course catalog gives descriptions more thorough than these brief summaries.

The theology major/minor can combine with other majors/minors in many interesting ways. Christianity is involved in a variety of endeavors besides Sunday morning worship, so theological training could come in handy in all sorts of areas such as non-profit/charity business leadership, healthcare, law and government, and media studies. The most direct areas of employment are teaching and parish work. A B.A. in Theology would be enough to teach in a catholic grade school or high school. It would also qualify one for jobs in youth or other parish ministry. One could continue study for the degree Master of Arts, which generally takes two years. In order to teach college level theology and write books one should plan on five years to pursue a Ph.D.

The Israelites are an ancient civilization that had a lasting impact on the world because they produced the books that became the Bible for all Jews and Christians (who also have additional books). They live on through the Jewish people, and Christians and Muslims claim spiritual descent from them as the first recipients of God’s revelation.

The word “Israel” refers to a person, a people, and a land. In the Bible, Abraham’s grandson Jacob is also given the name “Israel.” In general, the ending “–ites” means “sons of” or “descendants of,” so the Israelites are the people who claim descent from Israel the person. As a people the Israelites can be called the people of Israel or simply Israel. The land or territory in which the Israelites lived is also called the land of Israel or simply Israel. (If you continue Old Testament studies you will also learn that Israel can refer to the Northern Kingdom of Israel, in contrast to the Southern Kingdom, Judah.) The land and people of Israel are linked, especially in the Jewish perspective, because God promised to form a special relationship with one nation and make them secure in their own land. Christians and Muslims recognize this special relationship but also believe that God later expanded God’s promise to all ethnic groups and all territories.

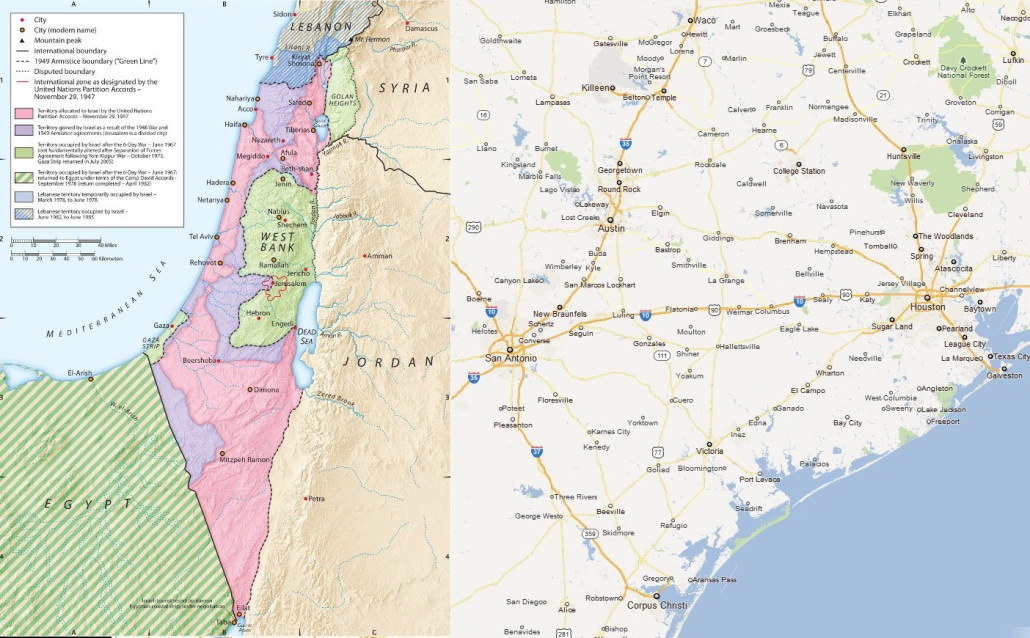

For Jews, the connection between the Jewish people and the land of Israel was always special, but was interrupted for most of the past two thousand years. In the twentieth century Jews made an effort to restore a homeland for the Jewish people with its own territory and government. This culminated in the declaration of independence of the modern nation of Israel in 1948. This territory is also the home to Arab Muslims and Christians who identify as Palestinians. The struggle to achieve peace between Jews, Muslims, and Christians in this territory continues to be difficult. The term “Israeli” refers to a citizen of the modern state of Israel, while the term “Israelite” refers to the ancient civilization. Though separated by about 2500 years, they are connected through the Jewish people.

The Israelites were never a large or powerful empire. Their economy was simple. We would hardly know they ever existed if not for the Bible. It is probably not a coincidence that they are geographically at the crossroads of the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Mesopotamia (Babylon, Assyria, Persia to the east), and the Mediterranean (Greece, Rome). Their ideas drew from many directions and spread in many directions, always by persuasion rather than force. The figure labeled Roman Empire shows the land of Israel in comparison with its ancient neighbors.

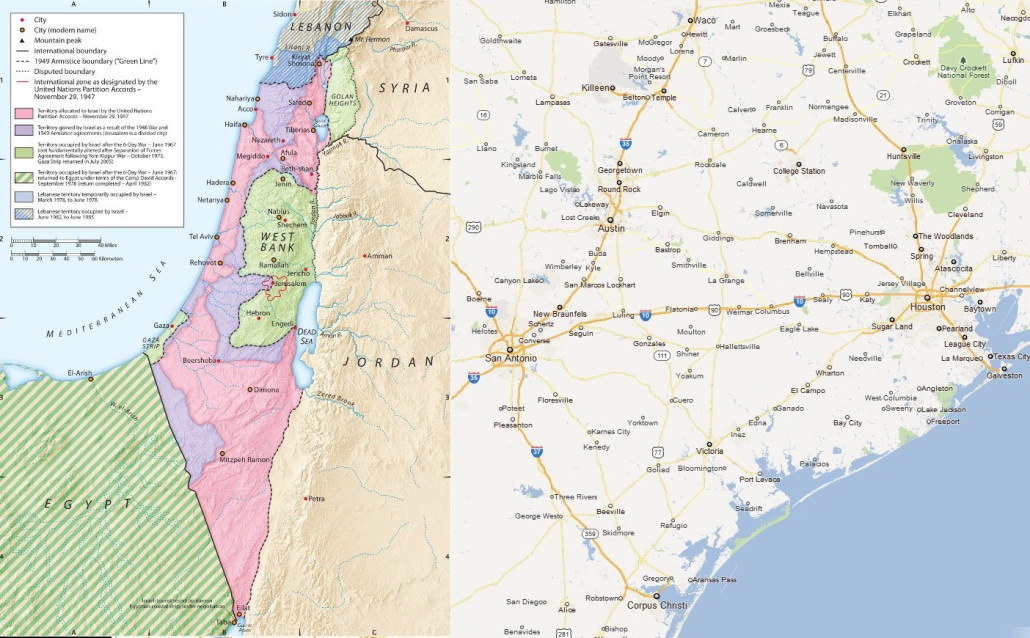

Just for perspective on how small the territory is, the maps of modern Israel and Texas in the figure labeled Israel and South Texas are on the same scale.

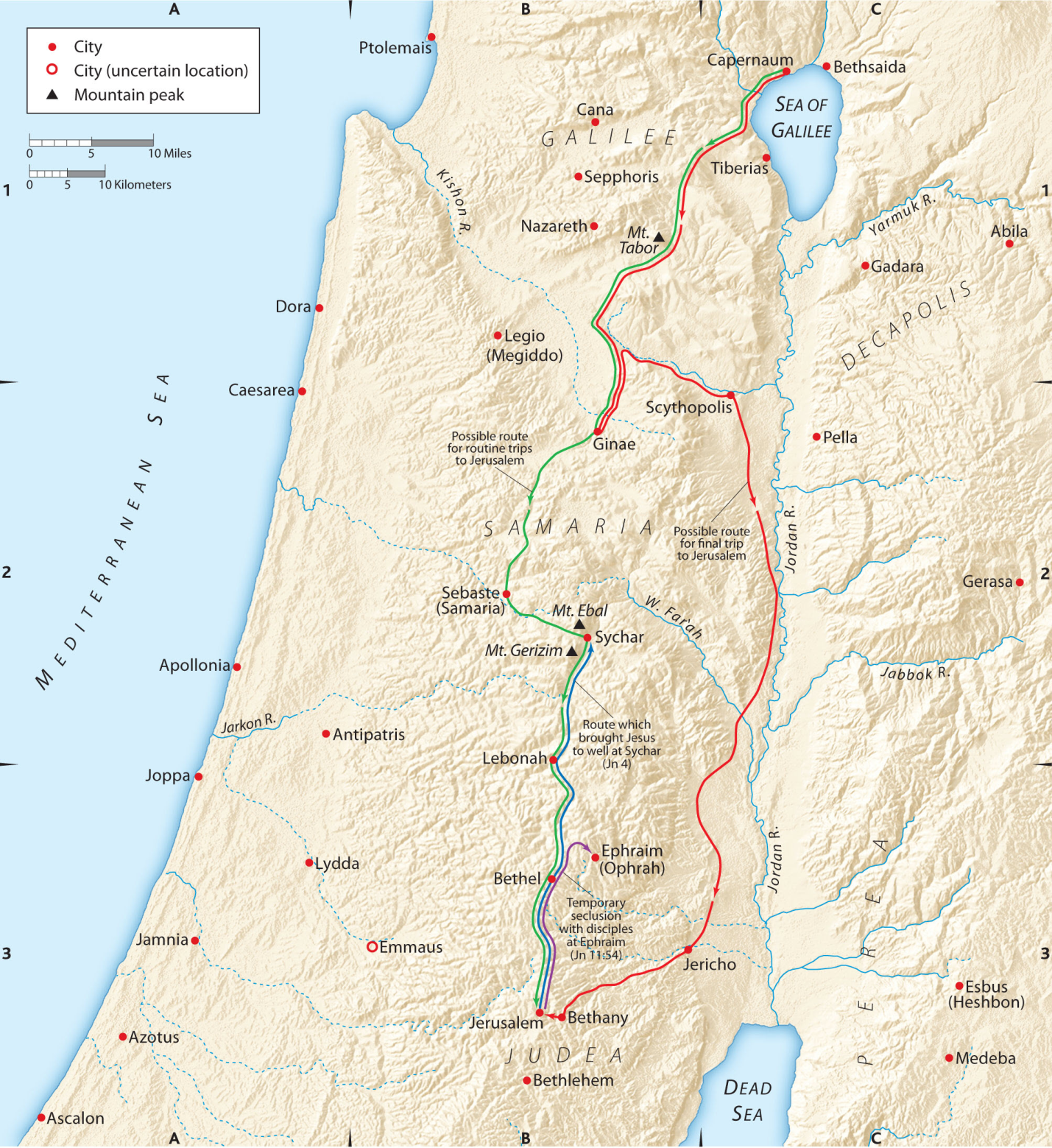

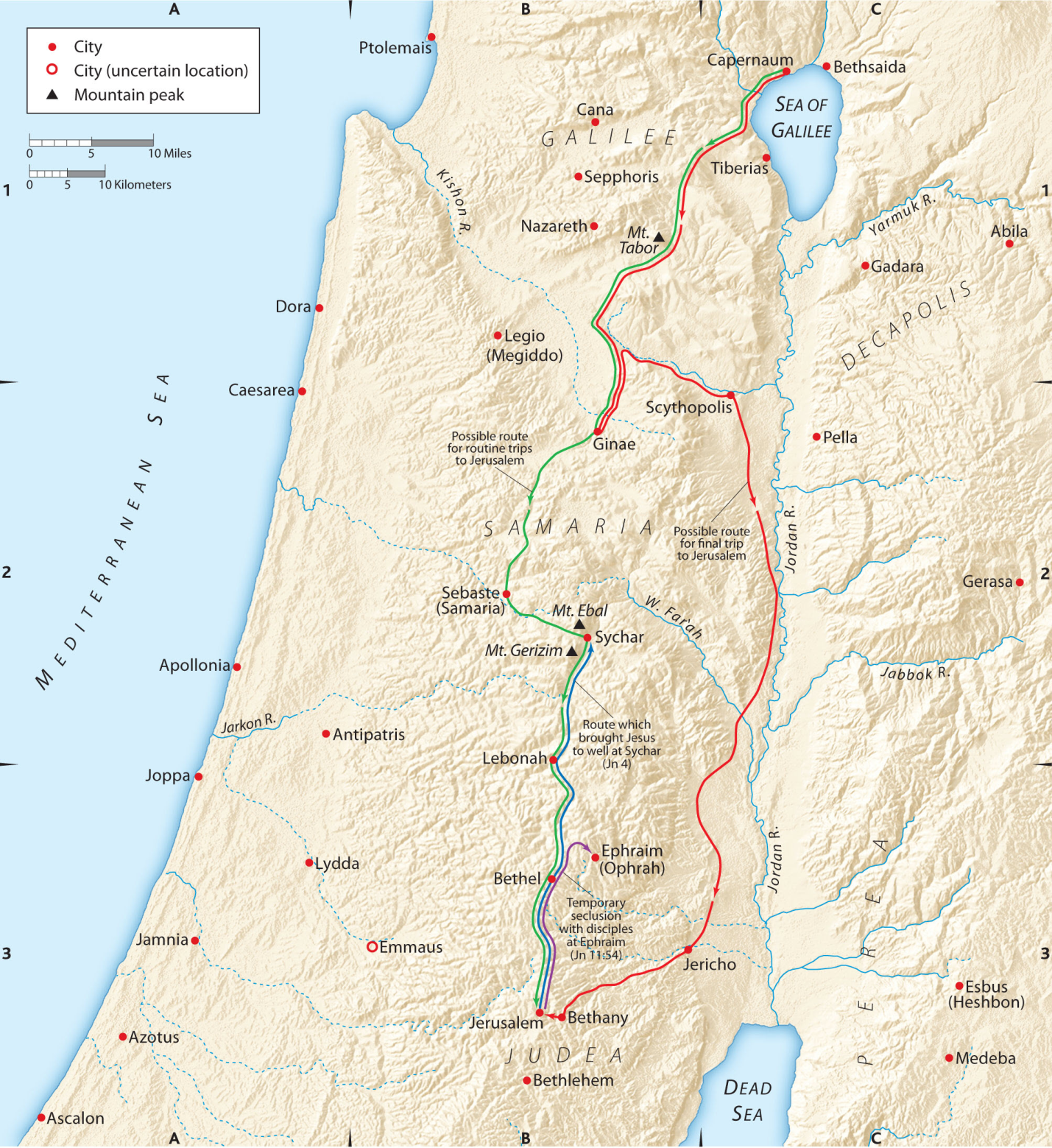

The figure labeled Israel at the time of Jesus shows the internal geography of Israel. Jerusalem is the most important city from the perspective of the authors of most of the Bible. Also look for the Sea of Galilee, the Jordan river, Nazareth, Bethlehem, and the Dead Sea.

The Bible offers legends and myths that give the pre-history of the people of Israel. The following dates begin with the earliest external record of the Israelites. Some of them are estimated or rounded. The ancient nation of Israel existed from 1250 to 587 BCE, but we are also considering the Judean and Jewish authors who produced the Hebrew Bible, the last book of which was written in 164 BCE.

Many ancient civilizations produced more art, literature, military strength, technological innovation, and intellectual innovation than Israel. Most of them were defeated or simply faded away with time, and ceased to exist. Israel survived as a people and a set of ideas because they managed to maintain their identity without a homeland where they were a majority, or a central governing body. The term Diaspora describes a people that has been dispersed from its original homeland, but maintains communal identity as small minorities spread over many places. In modern times, there are a number of examples of communities that are “from” a place that few or none of the members have ever been. The Jews seem to have been the first.

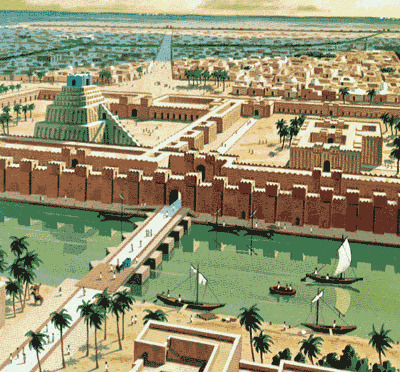

In 587 BCE the Temple and city of Jerusalem were destroyed and the leading citizens were taken into exile as captives. We call this the Babylonian Exile. They could have given up and assimilated to the culture that defeated them and now constituted the majority of people around them. Instead, they developed the idea that their God had not been defeated, but planned the exile for their own long-term good, and remained with them. They could maintain their beliefs and practices in their own homes and small communities, even though most people and all the people in charge had different beliefs and practices. The might of the victorious civilization did not amount to the correctness of their ideas and behaviors. This may seem obvious today, but it was a radical innovation that allowed a people to transition from a nation to a religion. Generally, we use the term “Israel” to refer to the phase when they existed as a politically sovereign nation, and the term “Judaism” to refer to a religion or people. The point is that it is the same people and the same tradition, transformed but not broken. Across Jewish history there were many occasions similar to the Babylonian Exile in that the Jewish people developed a geographic and leadership center, but the center was lost or destroyed, and the people lived on.

The Jewish people claim descent from the Israelites both biologically and spiritually. Although it is theoretically possible to convert, the basic definition of a Jew today is someone born of a Jewish mother (paternity tends not to be as certain or inalienable as maternity). There are certain beliefs and practices that are expected, but beliefs and practices do not define being a Jew the way they generally do for other religions.

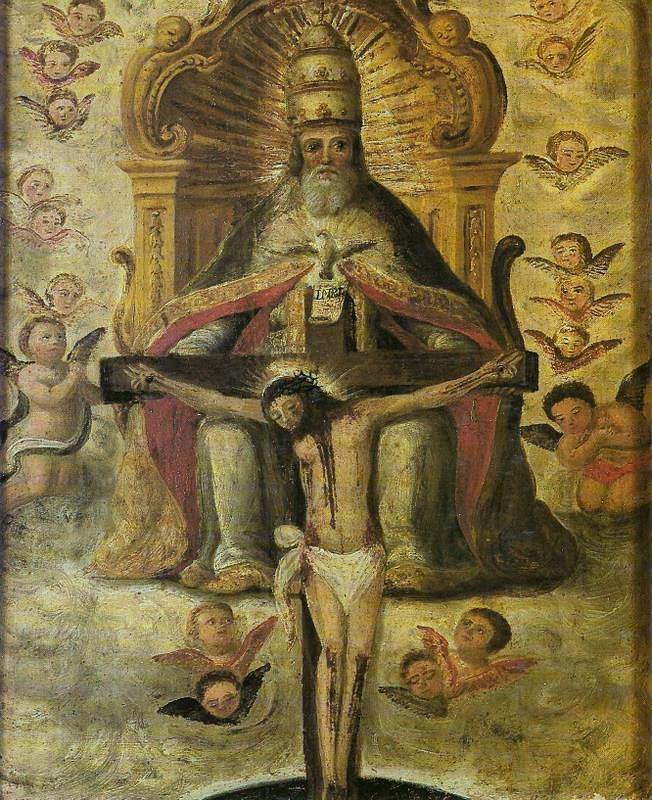

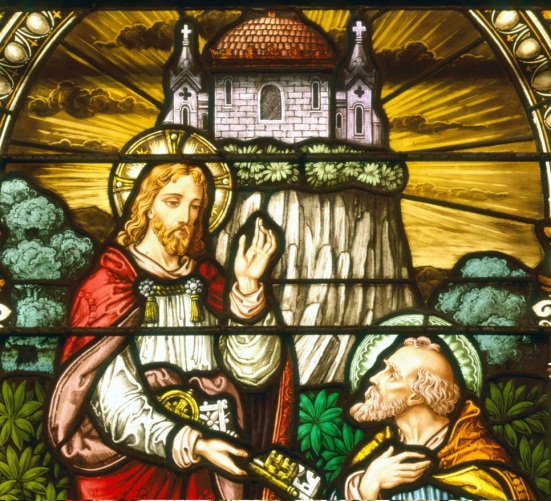

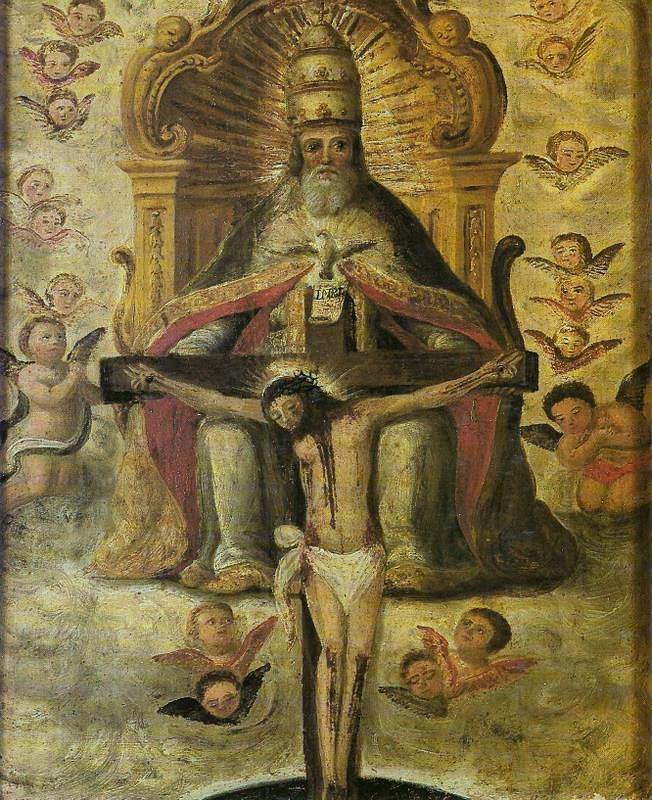

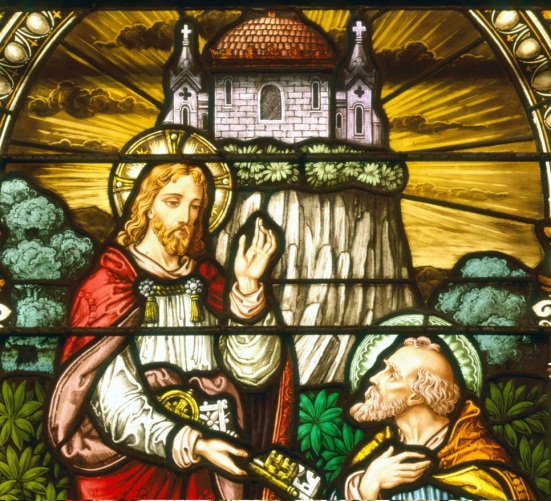

Christians also claim descent from Israel, but it is spiritual and not biological. It can be articulated in different ways, but the core Christian claim is that God once had a relationship with only one nation, and later made it possible for any and all nations to enter into a relationship with God, only now the condition was belief in God’s son Jesus, rather than birth descended from Jacob.

Islam also recognizes the biblical Israelites as part of salvation history. The prophets of Israel are revered as true and holy prophets who taught the same core message of Islam. The seal of the prophets of Islam, Muhammad, is considered descended from Abraham, the same family as Israel. Israel had its own prophets, but the prophet Muhammad is for all nations.

Most of what we know about the Israelites we know from the Jewish Bible. Even if we do not assume that the Bible is revealed by God or that its claims are true, reason alone establishes that it is a record of the literature and ideas of an ancient civilization. It tells us what questions they asked, and what meanings they found in their quests. It tells us how they viewed history, some of which can be confirmed by external evidence. The Bible was edited and interpreted for a long time, but careful examination of it tells us much about the Israelites.

Most of what we know about the ancient context of the Bible we know from archaeology. Archaeology is the study of or discourse about ancient things. For the most part, it means digging up old objects (called artifacts). Dirt accumulates over time, so generally the further an archaeologist digs down the further back in time the artifacts come from. Being buried in dirt tends to preserve “hard” objects, although we are missing anything soft. We can read very ancient writings that were written on stone or clay, and under the right conditions fairly ancient writings on leather or papyrus. People would also write on wax tablets, but those do not last. We can see the outlines of their buildings, their pottery, their statues, their metal tools and weapons. We can learn about their lives and diets from their skeletons. Taken together, we can know many things about the ancient world by piecing together various hints from their literary and physical artifacts.

Many ancient civilizations are worthy of study, and I hope you have time to learn about them. The reason a Catholic university wants you to learn about the Israelites is because our tradition believes they were right. They had true insights into God, who we are as human beings, and what God expects us to do. Christians do not accept everything they said, but do consider the questions they asked and the points they made worthy of consideration. Why should we trust them?

Christians differ on the details, but to begin we can say that all Christians believe that the Israelites lived in a special relationship with God and received revelation from God. Some Christians imagine God dictating the entire Bible word for word to humans who passed it on without change. Catholic Christianity understands God’s role in the production of the Bible as more complex, incorporating human language, expressions, literary devices, and other cultural assumptions. Catholicism teaches that the Bible is revelatory. God is revealed through the Bible. Sometimes revelation means prophecy in the sense of God speaking to humans. Other times, truths are made known to us through our own reason, our families and teachers, and the created world around us. The Israelites grappled with truth in the same basic set of ways that we do. The Bible did not just fall out of the sky and hit them on the head. They spent hundreds of years working on the ideas and articulation of the biblical books. The Catholic tradition holds that they did a particularly good job, with God’s help. Their questions and insights have been passed down to us for our consideration. Catholicism considers the Bible a reliable guide for understanding the central points of God’s desire for our salvation, but the human expression relies on ancient language, culture, historical and scientific assumptions that can be incomplete, flawed, or just plain wrong.

The Israelites were not the first to believe in a higher power. In fact, the denial of the existence of a higher power is not really found until modern times. Across human history a variety of conceptions of higher powers and spiritual realms have occurred. In the ancient Near East, which is the cultural neighborhood of the Israelites, the gods, by definition, had the following characteristics:

Although the existence of gods was not controversial in the ancient world, the Israelites were distinctive in their conception of what kind of god they have.

The stories about the gods in the ancient Near East are full of drama. The gods are far from perfect. The gods are all more powerful than humans, but some are more powerful than others. They may resemble our comic-book superheroes more than the God Christians teach today. They are full of gossip, intrigue, rivalry, competition, and conflict. At early stages they were conceived of primarily as forces of nature, such as the sun and water. The conception of the gods developed into imagery of politicians. They have councils, roles, and designated authority, but politics can often be manipulated.

The gods also have personal relationships, including love and jealousy. They mate and have children. The gods may be immortal, but they are born and have levels of age and maturity. They have certain needs, and can be bribed or persuaded the way one might persuade a human (gifts of food, flattery, deals).

So far you might be glad to not be worshiping such gods. One advantage of the ancient conception of the gods is that it was tolerant and inclusive. The ancients might say, “Your people worship a god other than the one(s) I worship? Fine, they’re both gods. We don’t all have to serve the same gods. It’s all good.” Some would even say that religious wars are impossible in such a system. I don’t think that is quite the case, but there is certainly some flexibility in the ability to add gods and imagine one gaining dominance while another “retires” and fades away. This is somewhat comparable to reverence for the saints in Catholicism. Many are deemed worthy or reverence, but it is not required that we all express devotion to the same (or any) saint.

Here is one more advanced point about the gods of the ancient Near East. The gods were powerful, but not all-powerful. They were subject to a still higher power of fate. Unlike the gods, fate is not personal and cannot be manipulated or changed. Like gravity, it is more like a law of the universe than a being or active agent.

Over time, not all at once, the Israelites would reject or seriously qualify everything in this section.

The Israelites conceived of their God as perfectly just. God behaves with perfect justice, and God expects justice of God’s people. Other gods had a sense of fairness and held the roles of judge or righter of wrongs. However, the Israelites pushed further with a God of perfect justice, which could not be manipulated.

God could be counted on to act justly and act in defense of those who do not receive justice on earth. By extension, God expects people to act justly.

Of course other nations had concepts of justice and laws, but those principles were not theological principles; they were independent of the gods. The gods were subject to certain social rules and consequences (for the most part), just as humans are subject to certain rules and consequences (for the most part). Anyone in the ancient world would have agreed that murder, adultery, and theft are not okay. Other nations had laws and punishments for certain crimes, but those were practical consequences. The Israelites were the first to present ethical laws as absolute commandments by God.

Moreover, the Israelites kept emphasizing justice as the most important attribute of God and the most important thing God expects of humans. Justice was foundational and more important than other aspects of religion.

Whereas the other nations conceived of gods who were fickle and opportunistic, the Israelites asserted that their God was fundamentally an ethical God.

All Jews, Christians, and Muslims are monotheistic. That is, we all assert that there is only one God. The oneness of God implies the unity of God, or even that all that truly is, is God. We have room for supernatural beings called angels, but they are clearly subordinate to God. On the one hand, this may be the most lasting insight into God that the Israelites had. On the other hand, this is a relatively late development in Israelite thought. Most of the Hebrew Bible does assume that other gods exist. Monotheism developed in stages.

The earliest stage is not very different from Israel’s ancient neighbors. Other gods exist, but one God is superior to all of them, like a king.

Some Jews and Christians will interpret these subordinate divine beings as angels, rather than gods. The early Israelites, however, called them gods. The idea that one God is king of all the other gods is not different from the idea that Marduk or Zeus is king of the gods. This early stage is still polytheism, the belief in many gods.

You might think if one God is superior to other gods then only the superior god should be worshiped and served. In fact, many polytheists focused on other gods who more immediately pertained to their needs. It is actually a separate stage to assert that only one God should be worshipped. Henotheism refers to being devoted to only one God, while acknowledging that other gods exist. The Israelites developed the idea that other nations have their gods, but Israel has an exclusive contract with the God of Israel. The God of Israel will protect Israel, but in exchange Israel may not worship other gods.

In this passage God is a “jealous” god. There are other gods to be jealous of. God demands to be ranked first. You can acknowledge the existence of other gods, you might even show them some respect, but you can’t put them above LORD, the God of Israel. Another passage demands absolute exclusivity, but for the original audience did not deny that other gods exist.

This translation is how the original audience, the ancient Israelites, would have understood the verse. Jews today would translate it a bit differently, in light of monotheism.

Monotheism is the assertion that only one God exists. Other gods that humans assert to exist do not exist. They are imagined. They might be demons, but they are certainly not even in the general category of God. The same verse given above as an example of henotheism is translated by Jews today as a statement of monotheism.

The absolute unity and oneness of God is an aspect of monotheism. Other, fairly late parts of the Hebrew Bible clearly assert monotheism.

Like many of the major ideas of the Israelites, the idea that there is only one God developed over time, through stages.

Many of Israel’s ancient neighbors thought of natural forces (such as sun and storms) as gods, or directly controlled by gods. The Israelites emphasized that the entire visible cosmos was created by God. It is in fact creation, and is distinct from the creator. God is therefore responsible for and in control of everything. In Greek philosophical terms, God is the first cause, the unmoved mover.

It is true that Israel’s neighbors had stories explaining how the earth came to exist as it does, and gods fashion things in a way comparable to creation. Israel’s understanding of their God as the creator stands out. God is purposeful and deliberate about creating in an orderly way. God does not face challenges or opposition. Furthermore, human beings are created with no ulterior motive. God is above the world as its creator; God is not a personification of nature. God does not need creation; God is self-sufficient. The Israelites will later have to account for evil (next unit), but the premise is that God is both good and responsible for all that is.

If God does not need anything, and God does not need us, why do we exist? What kind of birthday present do you buy for someone who already has everything, literally? According to Israel’s ancient neighbors, the gods were more powerful but not above bribery and influence. Israel’s God is generally more transcendent (above us), but God can only be so transcendent without being distant. People want to interact with their God. They want to be heard and they want some assurance or control over their relationship with God.

The Israelites developed the idea of a covenantal God. God does not need us, but God freely chooses to enter into a binding contractual relationship with us. A covenant is basically a contract. God does make demands as part of the contract, but not because of some need. God promises that if we live our lives a certain way (characterized by justice, love of neighbor, and exclusive reverence for God), God will reward us. Similarly, if we do not uphold our end of the contract, God will punish us until we return to compliance. Can we sue God for breach of contract? No. The point is we won’t have to. Does God need us? No. The point is that God chooses to make promises and to enter into binding relationships.

Israel’s neighbors imagined the gods as super-human, but basically through the extension of human (and animal) characteristics. The gods are like a strong human only stronger, like a powerful king only more powerful, fast as a bird only faster. Early Israelites continued to picture God in human form, but they moved away from thinking of God as even comparable to humans. They continued to use metaphors, but they recognized that metaphors for God are only metaphors.

God may be comparable to a father, protective mother, husband, warrior, king, or judge, but the comparisons are limited. God is not actually any of those. One implication is that God may be compared to a male human, but God is not male.

Israel’s ancient neighbors had little trouble explaining why bad things happen. The cosmos is full of drama and conflict. A natural disaster, such as a flood, could be explained as a turf-war between Land and Sea (capitalized to indicate that they are divinized). Losing a battle might mean our god was outwitted or overpowered by the enemies’ god. If something terrible happens to me personally, maybe my protector god was distracted or mad at me because I did not offer enough gifts (sacrifices) and flattery (praise). The Israelites, however, backed themselves into a corner by asserting that there is only one God in charge of everything, and that God is perfectly good.

Previously, for example with monotheism, we saw diversity in the Hebrew Bible as ideas developed over time. On this issue, we see diversity at the same time because different Israelites favored different ways of dealing with the same question. They came up with many ways of addressing the question of God’s justice. Some fit one context better than another. Some are challenging to accept. You may not like all of them.

First, let’s cover the language theologians use to discuss this issue. The word “theodicy” refers to the question of God’s justice in light of injustice/evil/suffering in the world. We have already seen the Greek word for god, theos (θεος). The second half of the word comes from the Greek for justice, dikē (δικη). The Israelites wish to maintain that God is just, but have different ways of defending that principle.

One classical way of formulating the problem is, “If there is only one God who is perfectly good and powerful, why does evil exist? If God is all-powerful and chooses to let evil exist, then God is not perfectly good. If God wishes to defeat evil but cannot, then God is not all-powerful.” If one wants to maintain that God is both omnipotent and benevolent then one has to explain why God would wish or allow evil to exist, or why God has not yet made it cease to exist.

Another classical way of formulating the problem is, “Why do the righteous suffer while the wicked prosper?” If the cosmos is governed by a just judge, then everyone should get what one deserves. Yet, when I look around me it appears that there are bad people with more prosperity and happiness than me, and good people who are suffering through no fault of their own.

One word we are not defining up front is “evil,” because the different answers seem to be focused on different conceptions of evil. Do we mean evil on the scale of 6.3 million Jews murdered just for being Jewish (the Holocaust)? Do we mean me not getting that promotion that I feel I deserved? A random flat tire on my way to a job interview? Do we mean the untimely death of my sister due to a freak accident? The timely death of my grandmother? All of these can be conceived of as evil, injustice, or suffering, at least at the time for the person involved.

The first, and most fundamental, Israelite contribution to this question is that God wills suffering for our own good, the way a parent punishes a child. God does not want us to suffer just as God does not want us to sin, but if we do sin then God chastises us so that we will repent. Once we repent the suffering will cease. If you are suffering the first thing you should ask yourself is what have you done wrong to deserve it. Change that, and the problem will go away. The suffering is ultimately just (we deserve it), and has a good meaning (to tell us we are doing something wrong) and function (prompt us to change our ways).

Within this basic explanation there are many variations depending on whether this system applies to individuals or communities, and whether it works instantly or over multiple generations. For the book of Deuteronomy, which is primarily associated with this explanation of God’s justice, it works for communities as a whole over the long course of history. If a single individual is wicked in a just society then the society will punish that individual. Only if society as a whole is wicked does it become necessary for God to step in. The Israelites struggled with the exceptions. Are a few wicked spared because of a generally righteous society? Are a few righteous punished along with the wicked majority? At least in Deuteronomy, God punishes with broad punishments like famine, plague, and invasion. It seems inevitable that such community-wide punishments would not necessarily target individuals within that community to the exact degree of their personal guilt.

The Israelites also struggled with the timing of the chastisement. A parent generally punishes a child right away (or at least as soon as one finds out, which theoretically should be immediately for God). However, Deuteronomy did not claim that the punishment immediately followed the sin, or that restoration immediately followed the repentance. These things moved slowly, and could take generations. On the one hand, this may be realistic. On the other hand, many Israelites did not think it fair that they should be punished for what their grandparents did, or that their repentance would not pay off until their grandchildren.

The book of Proverbs builds on the perspective of Deuteronomy, but applies it to prosperity within a person’s lifetime. Here the “suffering” is not on the scale of war and famine, but poverty or mere lack of success. The claim is that hard-working, righteous people do prosper in the long run, and lazy, wicked people fail. If there appear to be exceptions in the short term, one must look harder to see that everything eventually works out justly. Setbacks and challenges build character for the righteous, while success is hollow and fleeting for the wicked. Ultimately, there is no real injustice. Everyone gets what one deserves.

This perspective is controversial because it seems to suggest that the wealthy are wealthy because they deserve it, and the poor are poor because they deserve it. It is probably no coincidence that the book of Proverbs was written by some of the most privileged people in Israelite society.

Other parts of the Hebrew Bible, such as Ecclesiastes and Job, do not so much explain suffering in the world as challenge the human capacity to understand the explanation. The argument is that God’s justice cannot be understood by human beings. God may have reasons for causing good or bad things to happen to someone that humans do not and cannot understand. Maybe the sinner deserved it. Maybe the suffering will lead to greater happiness. Maybe it is part of God’s larger plan. We are not God, we do not know what God knows, and we are not as smart as God, so we cannot expect to understand or dictate what God should do. We should basically accept God’s plan.

The logic is strong but for many it fails to satisfy the basic human desire for an explanation. It also emphasizes accepting what happens over taking responsibility for overcoming injustice.

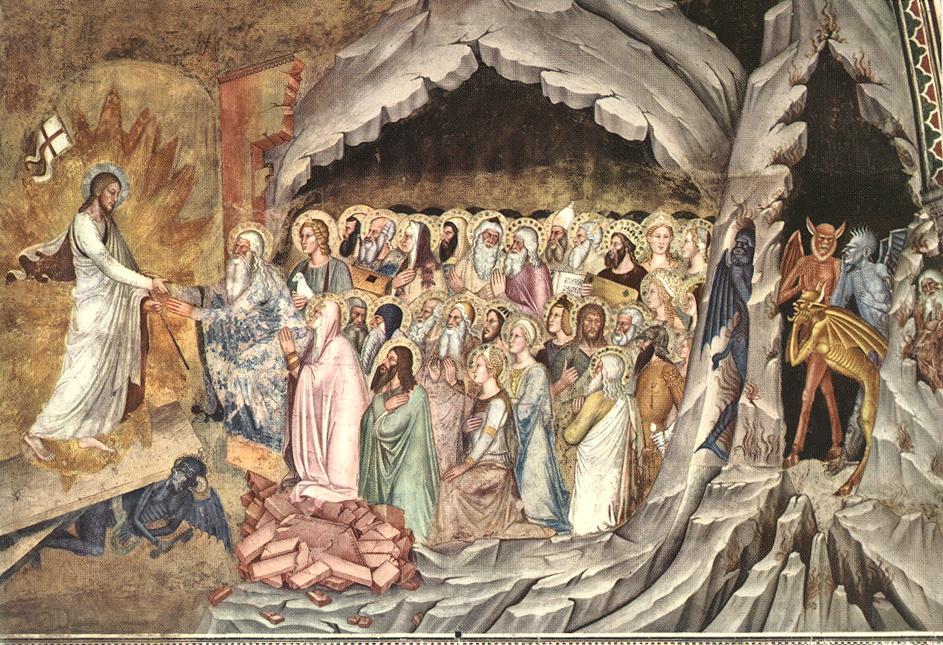

Deuteronomy was content to say that as a general pattern, over the community as a whole and history as a whole, suffering is deserved and meaningful. It seems that in the time of Ezekiel, many saw themselves as exceptions who did not deserve to suffer but were suffering because of wicked neighbors or ancestors. Ezekiel asserted that every individual gets exactly what that individual deserves. He completely rejected even the possibility that a righteous person might suffer or a wicked person get away with it. In response to the then-recent Babylonian invasion, Ezekiel asserted that God sent angels to mark and protect the righteous while the wicked were left to be slaughtered by the Babylonian army.

This radical assertion of God’s justice is nice in that we would like to believe in such perfect fairness, but it is hard to reconcile with the world around us. Ezekiel asserted God’s perfect justice more boldly than ever. Ezekiel himself did not imagine an afterlife in which injustice in this life would be compensated with radical justice in the next life, but it seems to be inevitable given his claims.

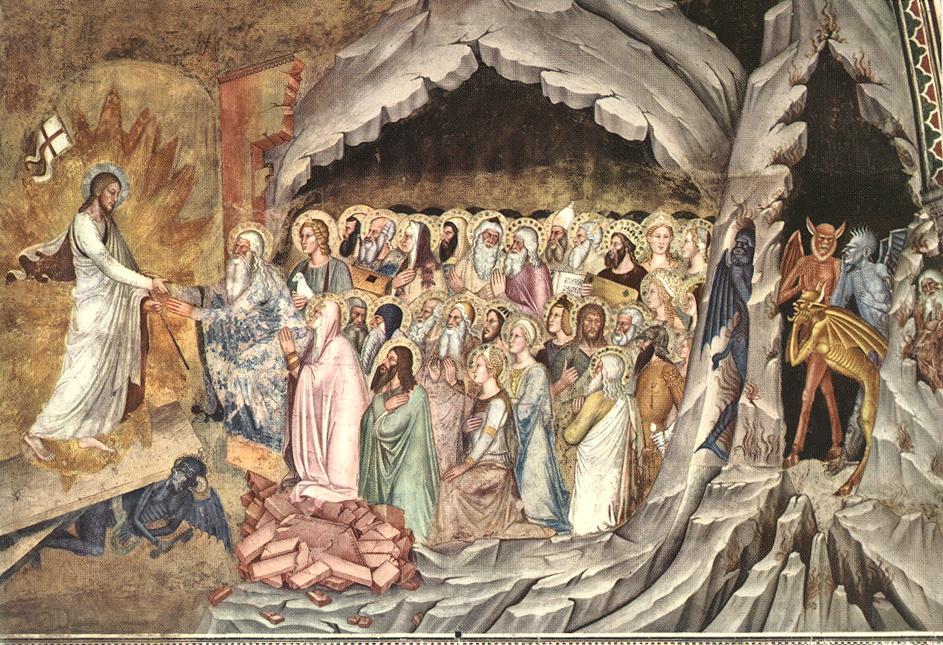

Today, Judaism, Christianity and Islam all believe strongly in an afterlife. They all believe that an individual’s soul and/or resurrected body will be judged directly and perfectly by God at some point after death. If a person was wicked and unpunished in the first life, punishment would be extra severe in the second life. If a person was righteous and persecuted in this life, the reward would be extreme in the second life. Remarkably, this idea developed fairly late. In the Hebrew Bible it is only found in the last chapter of the last book to be written, namely the book of Daniel, finished in 164 BCE.

This idea allows one to maintain God’s perfect and personal justice, as asserted by Ezekiel, in light of the injustice that appears so rampant. Daniel was written during a period of persecution, when it would be impossible to deny that wicked things happen to good people. Here I don’t mean just a flat tire, but being killed simply for the religion you practice.

Around the same time the idea developed that the evil which the righteous face in this life cannot be explained by chastisement, bad luck, or bad choices made by human enemies. The suffering seemed super-natural in its scope, power, and evilness. Even if there are no other gods, there are evil angels (or other cosmic forces) that are more powerful than humans, though less powerful than God. They are attacking God and God’s people, and temporarily they are succeeding. They are doomed to failure, but in the present they are doing just fine. There will be a judgment day when everything is set right, but for now God is waiting until that predetermined day.

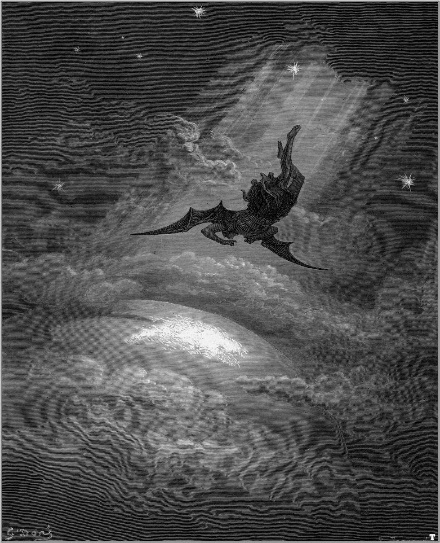

The general idea takes various forms, but it is most familiar in the idea of Satan, which developed more later. Satan, at least in later times, is imagined as one of God’s angels who rebelled against God, was cast out of heaven, and spends his time plotting vengeance against God and God’s people. Satan targets the righteous and helps the wicked. Quite the opposite of Deuteronomy, according to this model if you are suffering it is because you are especially righteous. This idea may sound like a return to polytheism in that there are super-human forces that battle and impact the human realm. The monotheistic stamp is the inevitability (though delayed) of perfect and radical intervention by an all-powerful and all-just God.

Chronologically, this solution goes more with the following unit on the early Jews and Christians. It is found especially in the apocalyptic literature, most of which was excluded from the Hebrew Bible.

One more concept was articulated later, under the influence of Greek philosophy, but is consistent with the Deuteronomistic view and its derivatives. The idea is that God did not create evil, but God did create free will and gave it to human beings. Free will gives us the power to choose. God wants us to choose good, but in order for there to be a choice there has to be an evil choice alongside the good choice. Evil happens because humans fail to choose the good. God could have eliminated the evil choices, but then it would be meaningless if, like robots, we follow the pre-determined script to do good. On a related point, some philosophers claim that evil has to exist because we could not know the good if there were not evil with which to contrast, much like “hot” is only understood in contrast to “cold.” Other ideas continued to develop over the centuries.

The ancient writers have a variety of ways of expressing their theological points. Try to match the passages below with the ideas outlined above.

A slack hand causes poverty, but the hand of the diligent makes rich.

Whatever happens, it was designated long ago and it was known that it would happen; as for man, he cannot contend with what is stronger than he. Often, much talk means much futility. How does it benefit a man? Who can possibly know what is best for a man to do in life—the few days of his fleeting life? For who can tell him what the future holds for him under the sun?

Some of those with insight shall stumble so that they may be tested, refined, and purified, until the end time which is still appointed to come. … Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake; Some to everlasting life, others to reproach and everlasting disgrace. But those with insight shall shine brightly like the splendor of the firmament, And those who lead the many to justice shall be like the stars forever.

The word of the LORD came to me: What do you mean by quoting this proverb upon the soil of Israel, “Parents eat sour grapes and their children’s teeth are blunted”? As I live—declares the Lord GOD—this proverb shall no longer be current among you in Israel. Consider, all lives are Mine; the life of the parent and the life of the child are both Mine. The person who sins, only he shall die. Thus, if a man is righteous and does what is just and right… if he has abstained from wrongdoing and executed true justice between man and man; if he has followed My laws and kept My rules and acted honestly—he is righteous. Such a man shall live—declares the Lord GOD.

When you have children and children’s children, and have grown old in the land, should you then act corruptly by fashioning an idol in the form of anything, and by this evil done in his sight provoke the LORD, your God, I call heaven and earth this day to witness against you, that you shall all quickly perish from the land which you are crossing the Jordan to possess. You shall not live in it for any length of time but shall be utterly wiped out. The LORD will scatter you among the peoples, and there shall remain but a handful of you among the nations to which the LORD will drive you. … Yet when you seek the LORD, your God, from there, you shall indeed find him if you search after him with all your heart and soul. In your distress, when all these things shall have come upon you, you shall finally return to the LORD, your God, and listen to his voice.

When the sons of men had multiplied, in those days, beautiful and comely daughters were born to them. And the watchers, the sons of heaven, saw them and desired them. And they said to one another, “Come let us choose for ourselves wives from the daughters of men, and let us beget children for ourselves.” And Shemihazah, their chief, said to them, “I fear that you will not want to do this deed, and I alone shall be guilty of a great sin.” And they all answered him and said, “Let us all swear an oath, and let us all bind one another with a curse, that none of us turn back from this counsel until we fulfill it and do this deed.” Then they all swore together and bound one another with a curse. And they were, all of them, two hundred, who descended in the days of Jared onto the peak of Mount Hermon. And they called the mountain “Hermon” because they swore and bound one another with a curse on it. … These and all the others with them took for themselves wives from among them such as they chose. And they began to go in to them, and to defile themselves through them, and to teach them sorcery and charms, and to reveal to them the cutting of roots and plants.

The Israelites did not spend much time writing creeds or statements of theological belief. The emphasis was on practice—how one lives one’s life. The beliefs covered above are always presented with the implications for what one should do about it. For the Israelites, the question of “who is God?” led to “who are we, and what does God expect us to do?” Thus, we conclude our treatment of the theological questions of the Israelites with what for them was the most important part. It should be noted that different parts of the Hebrew Bible emphasize different priorities about which practices are most essential for the Israelites.

The Israelites thought of themselves as a people called to live in a special and exclusive relationship with God. The part that most contrasts with their ancient neighbors is “exclusive.” Israel was expected to serve God alone, and conversely God’s best promises and blessings were only for Israel. It is typical for communities to build their internal identity and unity by establishing boundaries that define who they are not. If you think about it, many groups are most easily defined by what they are not or what they oppose. For the Israelites an exclusive relationship with God required strict boundaries.

For the Israelites, the most important thing was to not be Canaanite. The Israelites originated in Canaan so it was particularly difficult to create identity boundaries. Their language was the same, their architecture was the same. Some scholars believe the Israelites hated the economic injustice associated with the rich, elitist, abusive Canaanites. Some believe it was their sexual perversion that initiated the separation. Whether it was the original issue or not, the point most clearly emphasized in Israelite literature is that you cannot worship both gods. The God of Israel, LORD, cannot tolerate Israelites worshipping the god of the Canaanites, Ba‘al, any more than a married person can tolerate infidelity from a spouse. In most of the ancient world it was pretty normal to celebrate a festival to one god one month and another festival to another god the next month. The Israelite prophets demanded exclusivity. The Israelites were not allowed to go to the festivals of other gods, especially Ba‘al. This is the practical implication of what was stated above about henotheism and later monotheism.

One of the controversial conclusions that many Israelites drew from the importance of not worshipping other gods is the prohibition of intermarriage. Intermarriage means marriage between members of different groups. Today it might make a difference whether we are talking about different religious groups, ethnic groups, or something else. In the ancient world those distinctions were not so clear, as religion was closely tied to ethnicity. The Israelites feared that if you marry a non-Israelite your spouse will eventually persuade you to worship the other god, which would offend the God of Israel. Note that the problem is not that someone else worships another god, it is only if an Israelite worships another god. The Israelites debated how strict this rule was, with some saying it is okay if the spouse converts, and others completely ruling out the possibility. Intermarriage remains controversial today. Most Jews today fear that intermarriage will lead to dilution of Jewish identity and children who do not completely identify with Jewish heritage. Catholicism does not oppose intermarriage but only endorses marriages that are committed to raising the children Catholic.

Later in the course we will talk more about pluralism and relativism. Pluralism is a good thing in that it brings awareness and tolerance of beliefs other than our own. However, Catholicism opposes relativism, which would say that any religion is as good as any other, and what is true for one person may not be true for another. At this point we will just say that the Israelites did not seek to wipe out all religions other than their own, but they did believe that within their own people it was necessary to make a choice between one god or the other, not both.

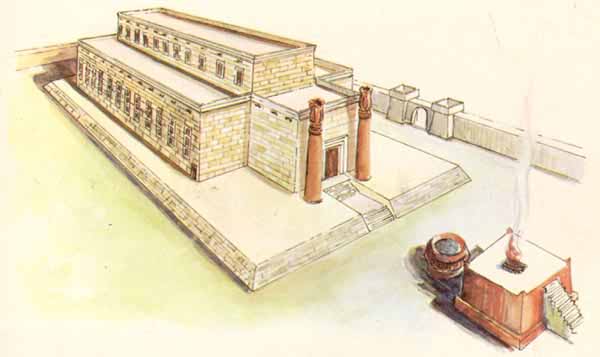

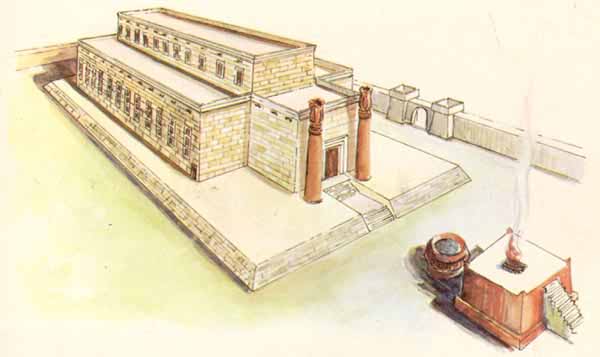

The Israelites did believe that they could address God from anywhere in prayer. Some of the Psalms could have been sung at the dinner table, while working, or on a journey. If there was a system of prayer and devotion in the home, we don’t know about it. The literature that was passed down is associated with the Temple in Jerusalem. The Temple was by far the best place to address God (praise, requests, thanks) and celebrate being God’s people. Although local shrines existed early in Israel’s history, the main teaching is that there is only one legitimate Temple, and that is the Temple in Jerusalem. If you did not live in Jerusalem, this meant a journey.

Given a particular need, an individual or family could travel to Jerusalem at any time. The main emphasis was on pilgrimage festivals, when the whole nation was supposed to gather in Jerusalem for a week at a time. These festivals were originally agricultural, celebrating the three major harvests in the early spring, late spring, and fall. The festivals would have been fun. The Israelites gathered from all over, saw extended family, sang, and danced. They brought offerings to God of meat, fruits, and vegetables. Fortunately, God only took a little and the people shared most of it. Sharing was an emphasis.

Today, Judaism celebrates the festivals in the home. Since 70 CE there has not been a Temple in Jerusalem at which to hold the festival. Catholicism has a concept of pilgrimage journeys to holy sites (often with more emphasis on the journey than the destination), but there is no requirement or a particular time or place to make a pilgrimage. The practice of pilgrimage continues most in Islam. The Arabic word haj is a variation on the Hebrew word for pilgrimage festival, hag. Muslims who are able are expected to journey to Mecca (the city in modern Saudi Arabia where Mohammed began to prophesy) at least once in their lifetimes.

The Israelites conceived of their God as an ethical God who expected ethical behavior from God’s people. The concept of an ethical God is enduring, but the specific standards of ethical behavior have changed over the millennia. Christians today are often disappointed when they read the Old Testament, particularly if they are expecting ethical guidance. In some cases the ideals seem impossible, and in other cases they seem barbaric by today’s standards. The Hebrew Bible can also be surprising in the way it mixes together practical laws for an impartial judicial system, with ideals that could never be enforced, such as “love God with all your heart” and “love your neighbor as yourself.”

The ideals for economic justice laid out in the Hebrew Bible may never have been fully followed. It was forbidden to charge interest on loans to fellow Israelites or to deny loan requests. Debts were to be automatically cancelled every seven years. That kind of financial plan will not get you too far in the business school, but the Israelites proposed a super-natural financial system, one in which God guarantees prosperity, particularly for those who share their prosperity. The goal was clear, “There shall be no needy among you—since the LORD your God will bless you in the land.”Deuteronomy 15:4

On several matters the Israelites were perhaps better than their ancient neighbors, but still hard to accept as ethical by our standards. It was a fundamentally patriarchal society. At least as far as the law was concerned, women were the property of the men who controlled them (father, then husband). Their rights were limited and could be overruled by men. They were excluded from religious authority and many of the major religious practices (at least the ones we know about from the Bible, perhaps they had others of their own). There are many double standards in which the expectations for women are different from those of men. In fact, the entire Bible is written from a fundamentally male perspective. There is much that is not acceptable today, but it is still possible for feminist Jews and Christians to read past these problems to find inspirational and positive messages for women. In particular, if we compare the biblical laws to the cultural context in which they were written, they are actually pretty progressive for their day, and seek to protect women. Compared to a society in which men can do whatever they want, the biblical restrictions on sexual relationships benefitted Israelite women.

Slavery is another issue on which the Bible’s standards do not seem ethical today, but were an improvement at the time. Although slavery was allowed to exist, the restrictions on slavery and rights of slaves were so liberal that slavery resembled contracted labor more than slavery. The Bible also calls for capital punishment for many offenses. Even here, the Bible is still progressive compared to its neighbors in abolishing capital punishment for property crimes (you can’t be executed for stealing).

The Israelites were also expected to maintain high standards of purity. One area of purity governed food. The Israelites were only allowed to eat meat and drink milk from clean animals, such as sheep and cattle. The animals prohibited as unclean are listed without explanation. One pattern seems to be that predatory or scavenging animals such as vultures were prohibited. Bottom-feeders such as crab, lobster, and catfish were also excluded. There is considerable debate as to why pork was prohibited. Perhaps they intuited that pork spreads disease more easily than other meats. Perhaps it started as a local custom that differentiated them from their enemies. Perhaps they recognized that pigs eat the same food as humans, competing for the food supply, whereas other animals eat grass, which is useless to humans. Perhaps it was the smell. Today Jews and Muslims agree that pork must be avoided, whereas most Christians think bacon greatly improves a breakfast taco.

Humans could also be in a state of uncleanness. It was not necessarily a bad thing to be in a state of ritual impurity, but it meant that one could not touch sacred things (such as the Temple) until a cycle of time and washing was completed. One was considered impure if one touched a dead body, skin disease, semen, or menstrual blood. One theory proposes that the common theme is death: skin disease represents the decay of a dead body, menstrual blood indicates a failed reproductive cycle, and semen anywhere other than a womb means it missed its intended target. The implied ideal is many children. Again, however, these normal parts of life were not inherently bad, they just meant restriction on contact with sacred things.

The Israelites recognized another form of impurity which was a bad thing, but affected the land and Temple more than persons. Moral impurity is a kind of pollution created by sin, particularly idolatry, adultery, and murder. Unlike ritual impurity, it is not enough to keep the persons associated with moral impurity outside the Temple. Moral impurity pollutes the Temple from a distance. God is holy, and holiness is incompatible with impurity. If moral impurity pollutes the Temple, God will leave, which is bad because then God will not bless and protect the Israelites. The only way to remove moral impurity from the Temple and maintain the holiness of the Temple is to wash it with the holiest material available to them. For the Israelites, blood is holy. It is the life-force, the divine spark that makes us alive. Shedding human blood was completely prohibited. Shedding animal blood was okay only if the blood was given to God. The meat could be consumed by humans, but never the blood. The holy blood was sprinkled, poured, or scrubbed on the holy objects of the Temple to make them holy. Blood could also be sprinkled on humans to make them holy. Judaism does not practice animal sacrifice since the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE.

Notice that the Israelites rejected the idea that God needs sacrifices for food (or bribery), but they found other reasons to incorporate animal sacrifices as part of their practices that maintained their identity and relationship with God. The blood of sacrificial animals was needed to maintain the holiness of the Temple. Food sacrifices were to be shared with others, especially the poor. The priests who worked in the Temple relied on a portion of the food offerings to feed themselves and their families.

The previous chapter introduced what happened to the Israelites. The ancient nation of Israel responded to the Babylonian Exile and Persian domination by developing into more the religion of Judaism than the nation of Israel. They got used to not having a king, a nation, or an army, and many of them grew accustomed to living as minorities among a dominant foreign culture. In the Persian Period (538–333) they still had their capital city (Jerusalem) and its temple to serve as the intellectual and spiritual center of Jewish life, even for those who lived far away. Over the centuries, Greek and Roman rule would make it harder for the Jewish people to maintain their identity. They had to ask themselves what were the essential ideas and practices that made them who they were, while they adopted and adapted new ideas. Some of the challenges came from the force of foreign armies. Other challenges came without violence, in the stories and ideas carried by merchants and travelers. The external challenges multiplied with internal strife, as different Jews took different positions on how to respond to foreign culture. By the first century CE, there were many different kinds of Jews. External and internal conflicts brought about the end of the Second Temple (70 CE) and the end of Jewish life in Jerusalem (135 CE). Unlike the Babylonian Exile, which lasted only a few decades, this loss of a central capital was largely permanent. The Jews who adapted to these changes did so by carrying their ideas in writing across many small communities, often no bigger than could fit in a house. Two major movements survived. The ethnic Jews who organized around teachers and interpreters of Jewish law became what we call Rabbinic Judaism. The other major movement rejected ethnic origin and Jewish law as the markers of membership in God’s people. For them God’s people were defined by faith that Jesus of Nazareth is Lord and the fulfillment of the Jewish law. They came to be called Christians.

One of the many ideas that spread from Greece to Judaism was the idea that the true self is the soul, which is temporarily trapped in the body. Dualism of body and soul is most associated with the Greek philosopher Plato (429–347 BCE). A particularly negative view of the body, in contrast to the soul or spirit, developed among Plato’s followers. The idea of the immortality of the soul fueled thought about the afterlife as a reward for virtue or punishment for vice in this life. This is a good time to outline some of the major views of the afterlife:

Other ideas about the afterlife were not taken up in Judaism and Christianity, but should be mentioned here to round out the discussion.

Exercise: match the following quotations to the corresponding view of the afterlife.

At his death he will not take along anything, his glory will not go down after him. During his life his soul uttered blessings; “They will praise you, for you do well for yourself.” But he will join the company of his fathers, never again to see the light. In his prime, man does not understand. He is like the beasts—they perish.

Death, I think, is actually nothing but the separation of two things from each other, the soul and the body… When a man who has lived a just and pious life comes to his end, he goes to the Isles of the Blessed, to make his abode in complete happiness, beyond the reach of evils, but when one who has lived in an unjust and godless way dies, he goes to the prison of payment and retribution, the one they call Tartarus.

The human body is a fleeting thing, but a virtuous name will never be annihilated. Have respect for your name, for it will stand by you more than thousands of precious treasures. The good things of life last a number of days, but a good name, for days without number.

Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, others to reproach and everlasting disgrace.

So also is the resurrection of the dead. It is sown corruptible; it is raised incorruptible. It is sown dishonorable; it is raised glorious. It is sown weak; it is raised powerful. It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body.

For the most part, Jews were challenged by Greek ideas under social pressure (peer pressure, the desire to fit in) and economic pressure (doing business with people who did things differently) rather than physical force. There were some exceptions, however, and Jews sometimes had to choose between preserving their way of life and their actual lives. Those who chose to die rather than compromise their values were considered martyrs. This became an issue under the reign of the foreign king Antiochus Epiphanes, and led to the Maccabean Revolt (167–164 BCE).

The Romans always demanded complete political submission to their military might, while tolerating the religious practices of Judaism. However, the line between religion and politics blurred with the idea that Roman emperors should be worshiped as gods. Refusal to worship the emperor looked (to the Romans) like political insubordination, and insistence on worship of the emperor looked (to Jews and Christians) like religious persecution. The Jews were often, not always, tolerated as an ancient religion and people who mostly kept to themselves. Christians, on the other hand, were seen as a new cult growing among Gentiles who formerly had worshiped the gods and emperors. They were persecuted more. There were several responses.

We know some Jews wanted to join Greek culture and made little or no effort to hold onto their Jewish heritage. Three key items were widely accepted as essential markers of Jewish identity that could not be compromised. (Of course many other things that Jews valued were not controversial with the Greeks.)

Other elements were important to some Jews but not others. Examples include the authority and leadership of the high priest and the Hebrew language. Some Jews living in Greek-speaking cultural centers started to think of Moses (author of the Jewish law) as a philosopher like Plato.

Another debate among Jews was whether non-Jews could join them. Many understood God’s people Israel as the biological descendants of Jacob, so placed little or no interest in people of other ethnic groups joining their ethnic group. Others concluded that if there is only one God then that God should be worshiped by all nations. They imagined all nations should eventually join the Jews.

Christianity started as a Jewish movement. Jesus and his disciples were Jewish. As the message spread, many non-Jews wanted to join. Some early followers of Jesus thought that a non-Jew who wanted to follow Jesus had to become Jewish and keep the Jewish laws such as circumcision, dietary laws, and the sabbath. The view of Paul became the dominant view. Paul said that God’s people are all those who are unified in faith in Jesus as Lord. Ethnicity and observance of the Jewish laws were not essential. Meanwhile, renouncing belief in Jesus as Lord or worshiping the Roman emperor as Lord was unacceptable.

Especially in the second century BCE, a number of factors we have already considered led to a strong conviction that the world as we know it is not the world God wants, radically so. Namely:

Many Jews developed the expectation that God would intervene to end the world as we know it and usher in a radically different age of justice. There was great variety in the details of how they expected that to happen. This unit will focus on Daniel 7, which epitomizes Jewish apocalyptic eschatology and was tremendously influential on early Christianity.

The term eschatology comes from the Greek eschatoi (εσχατοι) “last things” and logoi (λογοι) “words, discourse,” so is the discourse or words we use to talk about the last things. The classical definition specifies four last things, namely death, judgment, heaven, and hell. Theologians today often speak of eschatology as our ultimate hope as Christians, as in where do we hope this world is going and what God will do for it. I will be happy if you remember that eschatology is the theological discourse about the afterlife and the end of the world. If you think about it, those two things are distinct, but both pertain to the goal or end of a life as we know it and the world as we know it.

The funny thing is what we say about the goal or end of the world or life says a great deal about how we view the present world and life. At the negative extreme, one might view the world as so thoroughly corrupt that when God does intervene God can do nothing for it except destroy it completely and start over. At the positive extreme, one might view the world as so good that the only thing that remains is for everyone to realize God’s presence in the world as now only some do. Similarly, if this life is viewed as hopelessly unjust, then the focus is on escaping this life into an afterlife, in which the righteous will be radically rewarded (heaven), and the wicked radically punished (hell). The positive extreme is that we are already living in spiritual bliss. There are many degrees and combinations in between.

The term “apocalypse” is often misused to mean the end of the world or the catastrophic end of things. Apocalypse is actually a literary genre. A literary genre is a kind of literature, like sonnet, murder mystery, or vampire romance. The etymology of apocalypse is “uncovering of hidden things,” or “revelation.” Literature in the genre “apocalypse” uncovers hidden things about invisible agents (angels, demons) and places (heaven, hell), and historical patterns (day of judgment, end of the world). Along with parts of Daniel, the most famous apocalypse is the Apocalypse of John in the New Testament, also known as the Book of Revelation. In popular usage, the words “apocalypse” and “apocalyptic” are used to describe anything that is reminiscent of the Apocalypse of John. There are many apocalypses outside the Bible.

The word “messiah” comes from the Hebrew mashiach (משיח) “anointed one.” In Greek, the word is christos (χριστος), from which we get the word “Christ.” (Christ is a title, not a name.) The concept of an anointed one has a long history, and we will return to some of the later reflections on what exactly it means to say that Jesus of Nazareth is the anointed one.

Anointing people with oil is a very ancient ritual for marking a significant change in legal status. If a slave became free he or she would be anointed with oil. If a priest was ordained he would be anointed with oil. The most relevant change in legal status is that the king would be anointed when he became king (or king designate). During the monarchic period, the anointed one was the king of Israel, the descendant of David. During this period the claim was made that God promised that David’s descendants would rule as kings over Israel forever. There were even some bold claims about God’s protection of the king, using metaphors of God adopting the king as a son. That was all fine and good as long as there was a son of David ruling as king over Israel. When the monarchic period ended in 587 (the Babylonian Exile), God’s promise seemed to have been proven false. There were many responses. Some tried to restore the monarchy. Some tried to say the promise was conditional all along. Some tried to transfer the promise in some way. The interpretation most relevant here is that many held onto the hope that God would someday restore the monarchy of the son of David.

At first it was a relatively practical hope for an ordinary human king. As the cycle of hope and frustration continued the expectation became more radical. Many Jews came to expect that a supernatural king would usher in a new era of Jewish sovereignty and perfect justice. This eschatological king is usually meant when the word is capitalized, “the Messiah.” The idea of the Messiah becomes tied to eschatology and the expectation of a kingdom of God. Although the idea of the Messiah becomes supernatural, the Messiah always remains human. Eschatological scenarios in which God or an angel acts directly are not appropriately called Messianic if there is no one human agent who takes a major role. As we shall see, Son of David, (adopted) Son of God, King of the Jews (or King of Kings), Anointed One, Messiah, and Christ are all essentially synonymous titles applied to Jesus of Nazareth.

With or without a human king at its head, many Jews expected God and God’s people to be their own kingdom. The idea that survived the longest was the idea that the Jewish people can live their way of life under foreign rule and dominant cultures. For some, that was not good enough. They thought that God’s people should be free of foreign rule, and perhaps themselves be the rulers of the world. They looked at the great empires of the world (the Persians, Medes, Seleucid Greeks, Romans) and thought their power was inversely proportionate to their virtue. Why would God allow that? Shouldn’t the righteous people be the ones in charge? Surely God is getting around to defeating the current great empire and setting up the Jews in their place.

To be clear, the kingdom of God (or God’s people) was originally meant very literally as an earthly, political kingdom. This was true before Jesus, and well into the early days of the followers of Jesus. Many early Christians expected Jesus to come back soon, overthrow the Romans, and establish a political kingdom. As that did not become the case, Christians began to reflect on Jesus’ teachings about the Kingdom of God as something that can exist in their hearts, or in small communities of Christians sharing in a common life in the body of Christ. Some argue that the followers of Jesus came to understand the kingdom of God not as an alternative kingdom, but a critique of the very idea of domination in all aspects of life. Today most Christians will say that the kingdom of God is both already and not yet. It is already with us in the faith Jesus has given us, and remains not yet fulfilled until Jesus returns and makes manifest his victory over sin and death. To this we shall return. The term “realized eschatology” refers to the idea that the fundamental change (if not end exactly) in the world has already taken place.

The Book of Daniel is probably the last book of the Hebrew Bible (this chapter is actually in Aramaic) to be completed in about 164 BCE (some books in the Jewish Greek Bible, which became the Catholic Old Testament are later). It is set in the sixth century BCE, during the time of the Babylonian Exile. Although most Jews recognize the decree of Cyrus the Persian in 538 as ending The Babylonian Exile, Daniel seems to suggest the Babylonian Exile didn’t really end in the sense of properly restoring the kingdom of God. Daniel 7 uses the literary genre “apocalypse” to describe the revelation of the real pattern of history.

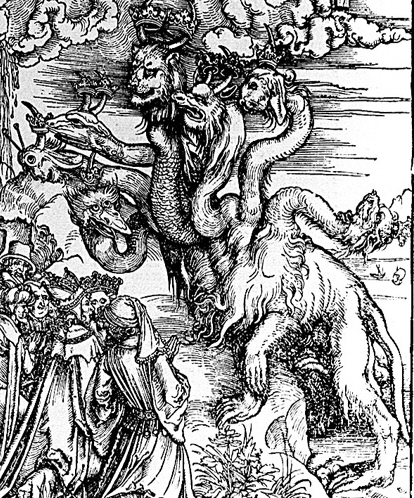

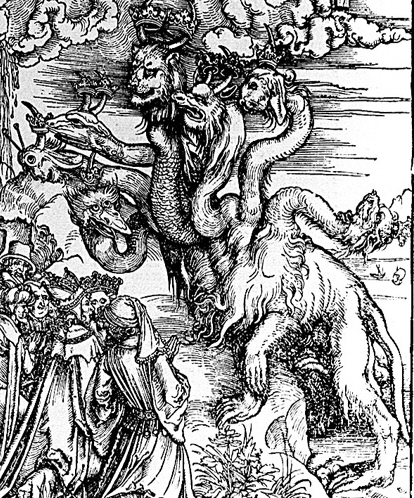

In the first year of King Belshazzar of Babylon, as Daniel lay in bed he had a dream, visions in his head. Then he wrote down the dream; the account began: 2In the vision I saw during the night, suddenly the four winds of heaven stirred up the great sea, 3from which emerged four immense beasts, each different from the others. 4The first was like a lion, but with eagle’s wings. While I watched, the wings were plucked; it was raised from the ground to stand on two feet like a human being, and given a human mind. 5The second beast was like a bear; it was raised up on one side, and among the teeth in its mouth were three tusks. It was given the order, “Arise, devour much flesh.” 6After this I looked and saw another beast, like a leopard; on its back were four wings like those of a bird, and it had four heads. To this beast dominion was given. 7After this, in the visions of the night I saw a fourth beast, terrifying, horrible, and of extraordinary strength; it had great iron teeth with which it devoured and crushed, and it trampled with its feet what was left. It differed from the beasts that preceded it. It had ten horns. 8I was considering the ten horns it had, when suddenly another, a little horn, sprang out of their midst, and three of the previous horns were torn away to make room for it. This horn had eyes like human eyes, and a mouth that spoke arrogantly. 9As I watched, Thrones were set up and the Ancient of Days took his throne. His clothing was white as snow, the hair on his head like pure wool; His throne was flames of fire, with wheels of burning fire. 10A river of fire surged forth, flowing from where he sat; Thousands upon thousands were ministering to him, and myriads upon myriads stood before him. The court was convened, and the books were opened.

11I watched, then, from the first of the arrogant words which the horn spoke, until the beast was slain and its body destroyed and thrown into the burning fire. 12As for the other beasts, their dominion was taken away, but they were granted a prolongation of life for a time and a season. 13As the visions during the night continued, I saw coming with the clouds of heaven One like a son of man. When he reached the Ancient of Days and was presented before him, 14He received dominion, splendor, and kingship; all nations, peoples and tongues will serve him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion that shall not pass away, his kingship, one that shall not be destroyed.

15Because of this, my spirit was anguished and I, Daniel, was terrified by my visions. 16I approached one of those present and asked him the truth of all this; in answer, he made known to me its meaning: 17“These four great beasts stand for four kings which shall arise on the earth. 18But the holy ones of the Most High shall receive the kingship, to possess it forever and ever.”

19Then I wished to make certain about the fourth beast, so very terrible and different from the others, devouring and crushing with its iron teeth and bronze claws, and trampling with its feet what was left; 20and about the ten horns on its head, and the other one that sprang up, before which three horns fell; and about the horn with the eyes and the mouth that spoke arrogantly, which appeared greater than its fellows. 21For, as I watched, that horn made war against the holy ones and was victorious 22until the Ancient of Days came, and judgment was pronounced in favor of the holy ones of the Most High, and the time arrived for the holy ones to possess the kingship.

23He answered me thus: “The fourth beast shall be a fourth kingdom on earth, different from all the others; The whole earth it shall devour, trample down and crush. 24The ten horns shall be ten kings rising out of that kingdom; another shall rise up after them, Different from those before him, who shall lay low three kings. 25He shall speak against the Most High and wear down the holy ones of the Most High, intending to change the feast days and the law. They shall be handed over to him for a time, two times, and half a time. 26But when the court is convened, and his dominion is taken away to be abolished and completely destroyed, 27Then the kingship and dominion and majesty of all the kingdoms under the heavens shall be given to the people of the holy ones of the Most High, Whose kingship shall be an everlasting kingship, whom all dominions shall serve and obey.”

28This is the end of the report. I, Daniel, was greatly terrified by my thoughts, and my face became pale, but I kept the matter to myself.

Technically the phrase “kingdom of God” does not appear in this chapter, but the kingdom of the holy ones of God develops into the idea of the kingdom of God. The idea that God was about to create God’s own kingdom in contrast to the wicked empires of the day was tremendously influential. Some Jews used this to justify revolting against the Seleucids and Romans. The Jews who followed Jesus adapted the idea to an internal reality in addition to a prediction of the future.

Notice that the titles “Son of God” and “Son of Man” are confusing and may appear to be reversed. The “Son of God” was originally a title of the human king, signifying that the king’s relationship to God was like that of an adopted son to a father. “Son of Man” originally meant a human but in this allegorical chapter starts to mean the opposite, an angel or cosmic being sent from heaven. Brace yourself for ongoing confusion because Christians will say Jesus is both a divine being sent from heaven as ruler of the kingdom of God (Son of Man) and a human descendant of King David (son of God).

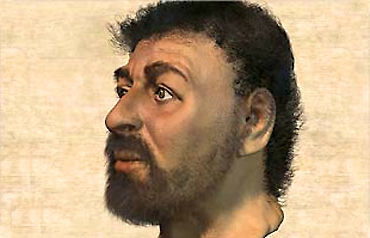

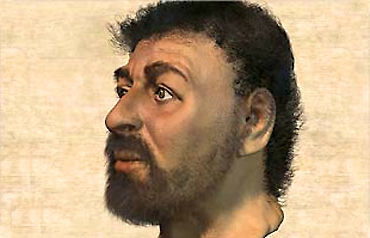

During the Roman occupation of Palestine many Jews looked for and found charismatic leaders who might lead them to bringing about God’s kingdom on earth. The most influential of those leaders is Jesus of Nazareth.

One of the major trends in modern (19th and 20th century) biblical scholarship is the effort to be objective. That is, scholars wanted to take the beliefs and opinions out of biblical interpretation, and excavate historical facts hidden in the text the way an archaeologist might excavate artifacts out of the ground, or even as a scientist might identify the structure of DNA. In the case of the New Testament, one of the major developments is the study of “the historical Jesus.” This means reconstructing the facts of the life of Jesus of Nazareth (and his followers) as objectively as possible, as one might write a historical study of Julius Caesar or Thomas Jefferson. In all cases, sources are biased, but critical historians read past the bias or correct for the bias to try to arrive at an objective truth, which generally means a truth that reasonable people can agree upon regardless of faith, opinion, or personal feelings.